Download your exclusive copy of the 4 Pillars Playbook: Creating Interactive e-Learning Instructional Designs to keep in your back pocket. Or, if you're ready to dive in, continue your journey below.

.png?width=500&name=e-book-cover-mockup-template-over-transparent-background-a9862%20(30).png)

Interactivity is the fundamental component that defines effective e-learning instructional design. By interactivity, we simply mean the repeating stimulus and response sequence of events that creates the possibility of learning in an online course. Interactivity exists in a wide and varying range of complexity, from simple navigation to intricate simulations. But all interactions are not equal in terms of how well they facilitate learning.

In the landmark e-learning instructional design book, Michael Allen’s Guide to e-Learning, industry pioneer and leader Dr. Michael Allen presents the CCAF, four components for Instructional Interactivity. Moving beyond the simplistic view of interactivity that appears in most e-learning, Instructional Interactivity strives to actively engage the learner’s mind to do those things that improve readiness and ability.

On one level, CCAF Design is strikingly simple for revealing what is necessary to create engaging and transformative learning interactions. However, there is also surprising complexity in how designers can master this model to create the best possible e-learning instructional designs.

Let’s explore this complexity and also establish some straightforward insights into how to best integrate CCAF thinking into your own digital learning design process.

con·text | kän’ˌtekst | noun

Embarking on an e-learning instructional design project, it’s all too easy to focus solely on getting the content “right.” Hours upon hours are spent staging content from subject matter experts (SMEs) and wordsmithing paragraphs of text to pass legal standards. Of course, content is significant. This approach only makes sense if we think training is just about transferring facts.

In reality, training is about communicating meaning, and meaning is conveyed―to a huge degree―through Context. We find richness and meaning in communication through Context as much as the literal words on the screen. We use our eyes to process visual cues, our prior experiences to activate existing mental models, and emotions trigger connections that foster long-term memories. In other words, the broader Context in which we encounter information has an enormous impact on how we learn.

There is always Context, whether we explicitly design it or not, but I’m afraid its very ordinariness causes Context to be too often overlooked in what e-learning instructional design needs to provide for effective learning. Even the blandest Context-free content presentation becomes a Context in itself, albeit a boring one—a neutral or academic Context that generally impedes the transfer of meaning. Too often, traditional Contexts are used largely by default or habit.

For example, a “book-like page-turning” structure may provide a navigation skeleton but, at the same time, conveys a monotonous impact that blends with every other piece of learning. Or there’s the standardized question model that only reminds the learner that the matter at hand is no more significant to them than the hundreds of versions of the same question they have already answered.

Context is every bit as important as the thinking that goes into the other aspects of instructional interactivity.

These are just a few of the many ways that design choices define Context.

How do you come up with the right Context? First off, there is no single “right” Context. There are many options for great Contexts for any particular Challenge, and there are also many poor ones. The key to coming up with a powerful Context comes from what you learn during the learning analysis:

What are the desired performance outcomes?

What is the performance environment like?

What are the conditions for success?

What kinds of errors get in the way of learner success?

Establishing relevance by creating an environment of meaning in which the lesson activities reside.

Letting story elements create interest, suspense, recognition, etc.

Representing human feelings and identities through media and personality to create a bond with the learner.

In a way that encourages practice and repetition that might be otherwise difficult to achieve.

That enhances motivation and entertainment while also achieving some of the aforementioned possibilities.

Bright Horizon’s Virtual Lab School makes extremely effective use of Context in its training for classroom supervisors. It would be all too easy to present guidelines and rules and then question the learner regarding their understanding. This knowledge is important but is useful only when understood in the Context of the Challenges and complexity that results from the unexpected and conflicting demands of an actual classroom with children present and active. In the e-learning course, before any content is delivered, the visual Context of the childcare classroom and the narrative richness in children going about their normal activities provides a compelling framework to Challenge the learner in an authentic representation of their everyday environment.

chal·lenge | chal’ inj | verb

chal-lenge | chal’-inj | noun

This is a very common-sense perspective of Challenge, but this is where we need some nuanced thought about meanings. This indeed is a prevailing idea of Challenge, but it is exactly what I think is wrong with so much of the interactivity (or more accurately, the questioning) that we find in e-learning. The learner is always put on the spot to prove something. Learners are rewarded for getting the “correct” answer and punished or shamed for doing something “wrong.” And this relentless Challenge of the learner’s abilities permeates everything, with pretests and posttests (largely meaningless), trick questions meant to obfuscate meaning (“which of these is NOT true”), and a determination to make sure failures are permanently recorded in the LMS student record.

Might I have been wrong in advocating for all these years that designers Challenge the learner? A little further reading in the dictionary reveals many other definitions of Challenge; this one is much more suited to our intent here.

YES! This is exactly it. The Challenge in CCAF is an invitation―an invitation to engage, to be fully involved, to join in, to take part. This invitation is not as an adversary as suggested by being tested and threatened, but rather as a partner. A good mentor challenges learners to explore, seek new ideas and skills, question their pre-existing ideas, and expand their understanding.

It is imperative as learning experience designers (LXDs) that we create a Challenge (the noun) that is sufficient, intriguing, relevant, and even uncertain enough to earn the learner’s full investment in the experience.

Creating good instructional challenges is not that difficult once we shed the idea that e-learning interactions are not there to test the learner but rather to mentor the learner.

Is the heart of the Challenge tied to something authentic and meaningful in the sphere of real-life performance? Or is it bound in some artificial construct that tries to distract rather than engage?

Does the Challenge require an actively engaged mind and purposeful actions? Or does its irrelevance urge and reward superficial strategies or thoughtless responses?

Is the Challenge rich in detail and does it offer an abundance of viable options in response? Or is it overly simplistic with a very narrow and trivial set of possible choices?

Does the Challenge encourage the learner to take responsibility for success, figure things out, explore, or take some risks? Are the learners' efforts rendered immaterial by over-explaining, giving away the answer, or by too easily letting the learner coast through without earnest effort?

Does the Challenge represent meaningful consequences that focus attention, sharpen strategies, and reflect the true results of performance failures? Or is the e-learning course ultimately indifferent regarding success or failure (aside from the irrelevance of generating a particular score?)

The Brooks Group incorporated several simple but effective elements to enhance the Challenge in their sales training. First off, the learner is challenged to perform, not just recall rote responses. Even though the interaction uses straightforward and typical response mechanisms, the learner is nonetheless challenged to try to solve the puzzle by selecting actions rather than simply matching item choices with literal content. There is a timer that creates an urgency to think critically and urgently to solve the problem before time runs out. Finally, each stage of the interaction has multiple parts, so then it becomes the learner’s added responsibility to actively pursue the end rather than following along passively and thoughtlessly.

ac·tiv·i·ty | ak-ˈti-və-tē | noun

Activity might seem like the most straightforward component in CCAF. In its most basic sense, it simply demands that learning is active; the learner must do something for learning to happen. Designing great Activity is at the very core of creating e-learning instructional designs that are effective. It’s often the place where interactions so often fail to achieve potential impact.

In the CCAF sense, Activity is at the very core of any instructional interaction. What the learner is asked to do has an enormous impact in creating focus, engaging full attention and senses, creating memories, and setting the model for transferring skills to the performance environment. Activity describes the specific gestures and actions that the learner undertakes in response to the Challenge. You can’t have an e-learning interaction without the Activity part; the trick is to design activities that facilitate learning.

Unfortunately, on the surface, the Activities available to an e-learning instructional designer to present for use are quite limited. Unless learners have specialized controllers or input devices at their disposal, learner gestures are pretty much limited to pressing a key or typing a sequence of letters or numbers, pointing or clicking a character or image on the screen, and moving a screen element from one screen location to another (mobile devices are limited in similar ways although the gestures are created directly

by fingers rather than via a mouse or keyboard). So unless the goal is to teach software gestures, the learning gestures have little to do with the actual desired performance outcomes. This is a problem because learning is enhanced when you practice in training what is expected in real-life performance. Clicking a, b, c, and d buttons as a learning Activity develops skill in answering multiple-choice questions. It does not necessarily translate to addressing the underlying real-world performance targets.

For me, this is where the instructional designer’s ingenuity and creativity most come into play. We can’t change the nature of computer input devices. But, we MUST create situations where the learner is convinced of doing something far more significant than the simple gestures on which the interaction is based. If a training course is intended to teach interpersonal skills, the learner must feel as though they are engaged in actual conversation with a partner. If a mechanical task is at hand, the learner must believe that an actual piece of equipment is being assembled or put to use. If solving a particular type of problem is the target of instruction, then all reasonable actions any learner might pursue need to be present and feel tangible. This is accomplished by crafting Context and Challenge to engage the learner so strongly that the illusion of meaningful Activity is made complete and convincingly.

Many Activity-weak interactions rely on too much reading. Why is this a problem? Reading itself can be really impactful, but in an e-learning environment there is no observable indicator that the e-learning Activity (i.e., reading) has even been done. If the designer has no mechanism to gauge if the core learning Activity has been completed, the whole interchange quickly falls apart, hence the huge number of learners who simply don’t read.

If you can do the Activity in an interaction without specific attention, it will do very little to create a lasting, meaningful thought. Doing the gestures to answer a traditional multiple-choice question can be done without even attending to a single detail of the Challenge at hand. It’s a really bad Activity simply because the designer can’t tell if the gesture is being done authentically or thoughtlessly. The result is learners who become great at guessing and mastering false but often successful strategies (like, “the longest answer is the correct one”).

A great Activity gets the learner to forget the artificial constraints of working online and creates the illusion of the Activity in the real world. Traditional online activities are good at suggesting an academic, testing-focused world. Instead, take advantage of your Context to build a convincing illusion that the learner is making decisions and gestures rooted in the physical world.

The learner benefits by expectations of proactive, exploratory experimentation, only made possible by designing the possibility of a wide range of gestures or outcomes from which the learner chooses and then executes. Any gesture undertaken by the learner should be the result of active thinking and focused action.

NexTech Academy’s award-winning Residential Technician Training builds technician competencies in the plumbing, electrical, and HVAC trade fields. The content combines technical knowledge with very specific tangible skills. The Leak Detection Methods e-learning module makes powerful use of Activity to communicate exactly what performance is expected. To understand how the standard leak detection tool should be used, the learner manipulates the image of the tool (dragging the image to points superimposed over an A/C unit) in a way that duplicates the target behavior (moving a leak detector tool physically around the A/C coils and noting changes in the readout).

feed·back | fēd’ˌbak | noun

Here’s a case where the dictionary definition needs no explanation. Feedback is indeed information about a person’s performance of a task, which is used as a basis for improvement. “Information which is used as a basis for improvement” — that’s the key. Too often, Feedback is tossed off with little thought, and a useless, “No, try again,” feedback message is given which is useless in any benefit it offers the learner. Or even worse, it simply answers and moves on. Feedback often communicates judgment status and some direction, but too rarely does it provide information intended directly to improve performance or enhance learning.

Instead, the Feedback should be the “payoff.” Instructional Feedback must provide as much helpful information and cues for improved performance. The focus should be on helping the learner succeed in the task, never just letting the learner off the hook. You might say that the primary point of an e-learning interaction is to connect the learner meaningfully with the instructional messages contained in the Feedback.

Feedback must be completely integrated into the Context. In fact, in thinking of options for your Context, the principal consideration in evaluating the most effective Context among alternatives is the extent to which it facilitates the impactful delivery of Feedback. What

is the point of creating a vivid immersive visual Context if you abandon the illusion at the exact moment of critical importance?

One of the biggest obstacles to meaningful content delivery is motivating learners to read content for meaning. Too often, when content is presented at the outset, the passages are simply skimmed or entirely skipped. This is especially true when the learner has no specific purpose in reading. But the moment of most heightened interest in the learner is after accepting and acting on a meaningful Challenge—that’s when you have the learner’s attention to deliver a meaningful content message.

Feedback is a reflection back to the learner of the impact and effectiveness of the learner’s Activity. Good Feedback doesn’t need to deliver the answer, but it must provide rich information and cues that encourage critical thinking that leads to active learning. Feedback should be rich and immediate and provide cues the learner can use to assess if things are moving toward success. Good Feedback should make the learner think harder. Judgment, on the other hand, is a concluding assessment of the learner’s performance. Judgment tends to close an interaction and transfers interest to what comes next.

Intrinsic Feedback is the practice of communicating through indicators embedded in the actual contextual learning environment, rather than through arbitrary messaging independent of Context. Intrinsic Feedback takes the ideas that drive simulations and heightens the degree to which successes and failures are communicated. Good Intrinsic Feedback supports transfer of new behaviors from the learning environment to the performance environment.

Correctness is not necessarily a particularly potent or even interesting indicator of success. As learners, we care much more if we have been appropriately engaged through a compelling Challenge about the real consequences of our choices. Representative real-life rewards or painful results create meaningful and emotional memories to reinforce learning.

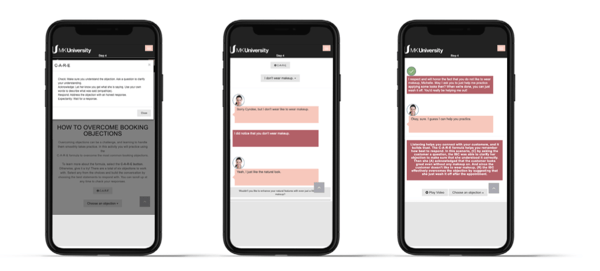

The Mary Kay University Independent Beauty Consultant Curriculum makes effective use of Feedback. Here in this mobile-compatible module, learners are given a very concise description of best practices for overcoming objections (the C-A-R-E Method).

The learner gets a chance to practice this method in a simulated conversation, based completely on Intrinsic Feedback presented in words and images from the prospective client. The learner can continue to navigate a successful conversation, learning from clues in the simulation and by reviewing the original C-A-R-E formula.

When the learner has solved the Challenge, Extrinsic Feedback confirms the learner’s success with a review of the steps that followed best practices.

And finally, the expert advice and encouragement is provided as the last step through a video discussion with an experienced practitioner.

Any discussion of the components of CCAF inevitably discusses each aspect individually and somehow linearly. This allows us to illustrate the particular meaning and significance of each CCAF component. The unintended outcome of this is that designers new to the process tend to design linearly and in order. In truth, the four components in the best instructional designs are integrated in a way that it is sometimes unclear whether some aspects of the design are Context or Challenge, or if the Feedback isn’t the Challenge for the next interaction. The good news is that it doesn’t matter. The process of sketching and prototyping, as an initial design methodology, forces the designer to think about the total impact of the e-learning design. Notice that the image used to describe CCAF is a circle. All four components are connected and should bear equal importance in your design thinking. A clear understanding of the role and significance of each component will allow you to engage in holistic design of masterful interactions.

Ethan Edwards draws from more than 30 years of industry experience as a learning experience designer and developer. He is responsible for the delivery of the internal and external training and communications that reflect Allen Interactions’ unique perspective on creating Meaningful, Memorable, and Motivational learning solutions backed by the best instructional design and latest technologies.

Ethan is the primary instructor for Allen Academy’s Certified Instructional Professional Program. In addition, he is an internationally recognized presenter on learner experience design and instructional design of e-learning, has written many e-books on creating effective e-learning, and is a frequent blogger. Ethan holds a master’s degree and significant doctoral work in educational psychology from the University of Illinois – Urbana Champaign.